If you have ever read Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, you may have remembered one or two general concepts: The “studium/punctum” interpretive model of an image, and the existence of the “winter garden” photograph of Barthes’ mother.

The former is what one of my professors referred to as the boring takeaway of the book; the easy “note card” version of what “should” be learned. It is an easily applicable, clearly definable, and altogether boring interpretive model.

What is more exciting, more mysterious, more beautiful, is the winter garden photograph: the photograph with which photography suddenly made sense to Roland Barthes. It was an image that he found of his mother, as he was looking for images after her death, of her as a small child. What to anyone else was a mundane photo of a little girl was to him a piercing and intense photograph that brought back, as real as any photograph could, the emotional connection to his mother.

Here I have a photograph that had such an effect on my mind. A photograph that transcended the mundane interpretations of what photography can be, the frustrating realities of what it actually is, and the hopeless desires for what it never will be. This photograph flashes into my mind and speaks clearly and decisively about not only what the photographer intended to communicate, but also the strengths of photography as a medium itself, and finally, it speaks referencing important truths of life.

I said, “I will guard my ways,

that I may not sin with my tongue;

I will guard my mouth with a muzzle,

so long as the wicked are in my presence.”

I was mute and silent;

I held my peace to no avail,

and my distress grew worse.

My heart became hot within me.

As I mused, the fire burned;

then I spoke with my tongue:

“O LORD, make me know my end

and what is the measure of my days;

let me know how fleeting I am!

These are the opening lines of Psalm 39, one of my favorite for the past few years now. The lines have driven my work forward in times when I question the worth of pursuing a definitive statement on anything, let alone trying to say something of worth about the most worthy thing in the universe. As I read these verses, it seems to me that the sin spoken of in these verses is not what comes out of David’s mouth, but what doesn’t. The sin is the desire to stop up words that might betray sin, but in doing so, words of truth are also withheld. As I have read and prayed over these verses, it is clear that the correction for this sin that David needs is to be made aware of his brevity, his inconsequence.

Behold, you have made my days a few handbreadths,

and my lifetime is as nothing before you.

Surely all mankind stands as a mere breath! Selah

Surely a man goes about as a shadow!

Surely for nothing they are in turmoil;

man heaps up wealth and does not know who will gather!

Back to the photograph. The image was made by Cathy Greenblat, a sociologist by training. Her photographic work deals primarily with the old and infirm, those near to death. If I had to describe the work as a whole in one pithy statement, it would be that someone with a good aesthetic eye and a great understanding of the issues in how we think about people near death has set herself on making photos that reorient the conversation. Having studied photography for some time and knowing what the taste du jour is in photographic aesthetics, I can say that while her photos are classically nice (well composed, well exposed, focusing on one subject intentionally, etc.) they lack a certain “contemporariness” that defines modern documentary photography.

Perhaps it could be best described as a rawness of formality and a refinement of conceptual vision. Ms. Greenblat’s work is simple and earnest in its presentation, I do not get the sense that her work is steeped in multiple layers of visual sarcasm and irony. That works to her favor in presenting her concept, but perhaps work against turning heads in the fine art world which I was pedagogically brought up in.

Now, Ms. Greenblat has an outstanding exhibition resume and has published several books of her photographs, so none of this is to suggest that she is an amateur or does not take her work seriously. However, it is satisfying for me to be able to look at photographs that don’t traffic the world of cynical fine art. They lack some of the cold sleekness of work I’m accustomed to looking at, but the photographs are good all the same. However, in coming across this photograph, I found it excellent.

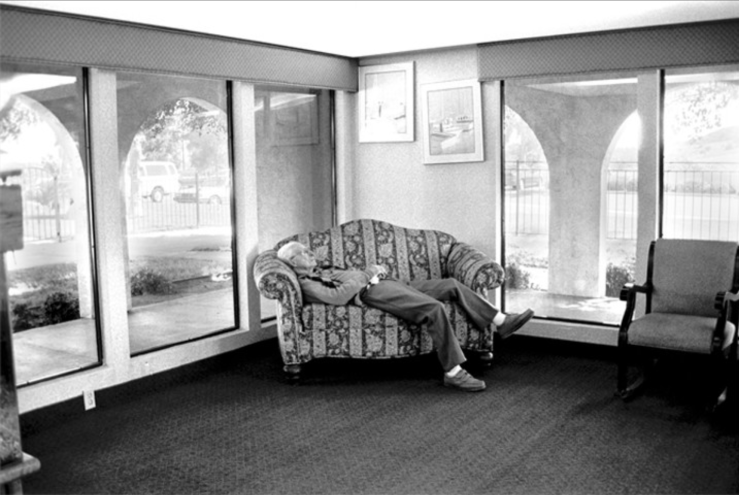

Compositionally and subject-wise, the photograph is unassuming. A man on a couch in the corner of the room. Yet, the elements of the photo root the viewer’s eye on the subject himself; he is laid bare in the center of the frame, nothing obscuring the path from camera to subject. Bits of empty furniture on the edges of the frame hold our gaze in the middle, and walls of floor to ceiling windows give us a sense that although the world is present, we are closed off and held in this room with this man.

And then the title, Arthur on the Sofa, Three Days Before He Died. It cracks like a gunshot before you in your mind if you will let it! Here we see a man, old, yes, but otherwise seemingly in a moment of leisure. Yet we have some vision into the future, knowledge that he cannot know as he reclines. He is three days from death. The black carpet below him and the white ceiling above him speak to these states, and he lays with one foot below, practically floating up.

I say that this photograph transcends the mundane interpretations of what photography can be because it has emotional resonance and force beyond a record of events. That it transcends the frustrating realities of what photography is is that this photograph goes so far beyond even the boring applications in a “fine art” sense, let alone the bucolic and trite applications in representing beautiful landscapes or “interesting” people (what a gross description when in reference to photography).

But finally, it is something aside from the desires of what photography can be; it will not bring this man back to life. The photograph cannot be titled truthfully and give this man new perspectives to change his course or set his affairs in order in his remaining three days. The photographer and the subject participated in something unbeknownst to them at the moment of capturing that photo. One may hope that the photograph can bring back to life, either the dead person or the passed moment, but it cannot. But this photo stirs the senses, quickens the mind, and brings into a view “…the measure of my days, [how] fleeting I am!”

That is why I say that this photograph begins to reference the important truths of life. Back to Psalm 39:

“And now, O Lord, for what do I wait?

My hope is in you.

Deliver me from all my transgressions.

Do not make me the scorn of the fool!

I am mute; I do not open my mouth,

for it is you who have done it.

Remove your stroke from me;

I am spent by the hostility of your hand.

When you discipline a man

with rebukes for sin,

you consume like a moth what is dear to him;

surely all mankind is a mere breath! Selah

In thinking about death when considering the importance of my work, I must consider my own. I must consider what it would feel like to cough up blood one morning and be diagnosed with terminal cancer before the sun sets. I consider it often when I ride a bike, the vision of a car running their red light into my green, and what it may feel like to be hit from the side at full speed. I wonder what it would feel like to have only a vague sense of my life behind me, and only days or weeks before I pass away. What it would feel like to have no prospects of what people call a meaningful life or experience ahead of me, but to consider the decades of my life behind me and what they have counted for.

I consider all these things not for a morbid purpose, or because I take some pleasure in them, but shudder at the thought. I would hope in the first case that the stark reality of having only a few months left on this Earth would give me great boldness to proclaim the only hope I have in life and, inevitably, in death: that Jesus Christ is who he said he is, and that he came to pay the penalty for my sin through his death and save my by his resurrection. It is a great burden, as David wrote,

“I was mute and silent;

I held my peace to no avail,

and my distress grew worse.

My heart became hot within me.

As I mused, the fire burned”

Yes, it is a great burden to try to hold within you this reality. It is sin, it is a quenching of the spirit, to hold down the words that “the saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Jesus Christ came into the world to save sinners, of who I am the foremost.” I don’t want to equivocate on these points, I don’t want to give the impression that I think anything else is worth striving after. “And now, O Lord, for what do I wait?My hope is in you.”

How could it be in anything else? For what do I wait to share with you this good news? In thinking of what these portents of death could be in my own life, and hoping that I would use them for great boldness in proclaiming the gospel, I also think of how much I have bit my tongue and withheld bold words for the sake of Christ, and what a sin this is, what little faith is displays in the power of God to save a sinner, even one like me. “No”, I would say to myself “I should not go on about such things, lest I look like a fool,” or even more piercingly, “lest I be shouted down and question my own faith” as if the validity of what I would preach were contingent on my ability to make an argument for it. But even more than all this, I am timid when it comes to speaking truth in this way. And this is a message of truth and beauty that requires not timidity, but boldness that is enabled by Christ’s work, not of my own cunning or eloquence.

Beyond the strivings of various importance of this world, from trivial things such as sports or entertainment to significant things like raising a family and loving your neighbors, beyond our own ambitions or shame or regret or need for validation. Beyond the pain of our failures and the joys of our successes. Although Christianity speaks to these things, there is still something worth considering beyond those things. Beyond our egos, far beyond this moment, there comes a point where we all are three days from death. And beyond death, then what? Is it not worth thinking seriously about these things from time to time? In what do we place our hope, and how then shall we now live considering that after all we chase after, after all we hope to build in our time, we all will sit, stand, lay, laugh, hope, dream, sleep, or eat on our third day until death.

If you can forgive the turn of phrase, it is worth remembering that Jesus too lived out this reality three days before his death as he faced being handed over by his own people to the Romans. In these moments, he prayed even to the point of sweating blood that the cup of the fate of death and the wrath of God pass from him. Yet he submitted himself to the will of the father and three days after his death rose in victory. For that reason, he is worth taking seriously, yes, even submitting to. Jesus is not an abstract notion or an impactful story or a teacher of good feelings and positive ways of treating other people, He is the son of God and makes exclusive claims to being the way, the truth, and the life.

I pray that if you have never considered these things, that you might think well on them. I’m not sure if Ms. Greenblat is a Christian or not, but in her work there is a clear and resounding truth that is worthwhile to consider. If you would like to discuss these things more it would be my pleasure to do so.

Wow Nick! What a powerful, well thought out and well written testimony. What a blessing you have created for those who read and contemplate on your words just as you contemplated on those of the Psalmist!

Thank you Uncle Phil!